The best history books are packed with vivid details about characters and events (sometimes prompting readers to say a good history “reads like a novel”). But reconstructing scenes and events from hundreds of years ago when only the scarcest of evidence has survived can be painfully difficult. Often the only surviving archival evidence is a brief recollection — a letter, a journal entry — from a single observer or participant. As Paul Schneider writes in his book Brutal Journey, what we know today about even significant historical events can be a “mosaic of pedigreed ‘facts'” that offer “a plausible rendering of the story” — but there are always, Schneider adds, “some tiles missing from the mosaic.”

The best history books are packed with vivid details about characters and events (sometimes prompting readers to say a good history “reads like a novel”). But reconstructing scenes and events from hundreds of years ago when only the scarcest of evidence has survived can be painfully difficult. Often the only surviving archival evidence is a brief recollection — a letter, a journal entry — from a single observer or participant. As Paul Schneider writes in his book Brutal Journey, what we know today about even significant historical events can be a “mosaic of pedigreed ‘facts'” that offer “a plausible rendering of the story” — but there are always, Schneider adds, “some tiles missing from the mosaic.”

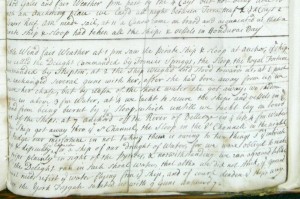

It is a rare and thrilling treat to uncover two or more separate, independent descriptions of an event that occurred hundreds of years ago. In my research on Philip Ashton’s odyssey and the pirate crews of Low and Spriggs, the logbooks of the British warships that battled with these pirates, still preserved even three hundred years later in the National Archives in London, often provided important additional insights to events described by pirate captives and other seafaring witnesses. These rich logbook entries helped me reconstruct, for example, a nearly fatal battle between the pirate Francis Spriggs and the warship HMS Diamond on August 31, 1724. That morning, Spriggs and his consort, the pirate Richard Shipton, were sailing near the coast of present-day Belize when they were surprised by the Diamond. The journals of two captives aboard the pirate ships at the time mention the battle but provide only the barest of details, mentioning that they encountered the Diamond and that Shipton and Spriggs were forced to separate as they tried to escape. But there were a number of trading vessels in the area that day, which yielded several other eyewitness accounts. One report comes from men aboard the Joseph Galley, a vessel from London that had come to Belize to take aboard a shipment of logwood. Another account was provided by a sea captain named John Cass, who returned to Rhode Island about three months later. What’s more, the specific details included in the actual logbook kept daily aboard the Diamond truly bring the events to life. “Little wind fair weather,” begins the logbook entry for Monday, August 31. “At 1 pm saw the pirate ship & sloop at anchor….at 2 the ship weighed [anchor] and stood towards us.”

The battle began only a little while later with a blistering exchange of cannon fire. Spriggs’ crew initially fired seven or eight shots at the Diamond and Shipton’s men fired at least twice. But the Diamond returned fire on Spriggs and came close to ending his career as a pirate then and there — at least two of the Diamond’s cannon blasts struck Spriggs’ ship head-on, ripping off his bowsprit and tearing away the front edge of his foresail. Half a dozen men aboard Sprigg’s ship were killed, and others were seriously wounded, some of them losing an arm or a leg. Clearly outmatched, Spriggs turned to flee. The light winds made it hard for him to pick up any speed, but they also made it impossible for the Diamond to catch up to him. Eventually Spriggs navigated his ship into some shoal waters among the cays that, at many points, were only twenty feet deep or less. As a result, the Diamond was unable to capture Spriggs. “We gave her chase,” the captain of the Diamond recorded in his logbook, “but by reason of the shoal water she got away.”