What surprised me the most, perhaps, while researching my book on Philip Ashton was discovering just how common young captives were aboard pirate ships during the early 1700s. Ashton’s story stands out because of its spectacular details — a young fisherman, captured by one of the worst pirates of the era, escapes and survives as a castaway on an uninhabited Caribbean island. But the more I pursued Ashton’s story, I uncovered the reports of dozens of other young men who were captured by pirates during this period — including many who sailed with Ashton — and who were forced at gunpoint or through ceaseless whippings to sail with these lawless crews.

What surprised me the most, perhaps, while researching my book on Philip Ashton was discovering just how common young captives were aboard pirate ships during the early 1700s. Ashton’s story stands out because of its spectacular details — a young fisherman, captured by one of the worst pirates of the era, escapes and survives as a castaway on an uninhabited Caribbean island. But the more I pursued Ashton’s story, I uncovered the reports of dozens of other young men who were captured by pirates during this period — including many who sailed with Ashton — and who were forced at gunpoint or through ceaseless whippings to sail with these lawless crews.

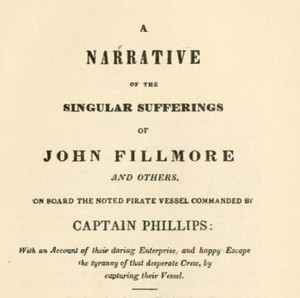

Almost as famous as Philip Ashton was another young man named John Fillmore, also a fisherman from a small village in Massachusetts, who was captured in 1723 by the pirate John Phillips. This month marks the anniversary of the death of John Fillmore (February 22, 1777), who lived a full life after surviving his pirate capture and would become the great-grandfather of future the future U.S. president, Millard Fillmore. In fact, President Fillmore was said to be familiar with his great-grandfather’s experiences as a pirate captive and may have owned the sword that once belonged to the pirate captain John Phillips — a sword John Fillmore was given for his role in one of the most dramatic uprisings against a pirate crew in the history of the Atlantic.

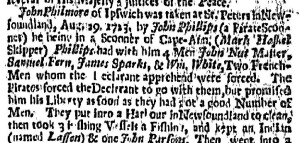

Fillmore was one of the first captives taken by John Phillips and his fledgling pirate crew. Just twenty-two years old in 1723, Fillmore had grown up near Ipswich, Massachusetts, a small coastal village about twenty-five miles north of Boston. Like Philip Ashton and many other young men forced aboard pirate ships, Fillmore’s narrative about his captivity recounts a seemingly endless stream of brutality. Fillmore repeatedly asked to be set free, but every request was denied. Instead, he was forced to help sail the ship, to move heavy weapons, casks, and equipment off captured ships, and beaten with a whip or sword for any perceived infraction. Many of the men aboard Phillips’ ship — not only the captives but some of the pirates, too — soon became tired of Phillips, the short-tempered and ferociously-violent captain. “Phillips was completely despotic, “Fillmore later recalled, “and there was no such thing as evading his commands.”

Fillmore quickly learned that the pirate captain John Phllips was not to be challenged. One of the vessels Phillips’ crew captured in early 1724 had some geese and hogs aboard, which presented the tasty prospect of fresh meat to men who spent virtually all of their time at sea eating dried and salted food. Phillips demanded the live animals, but the ship’s captain refused and struck Phillips with a handspike. Phillips quickly drew his sword and plunged it into the captain, killing him. This was only months after Phillips killed one of the initial members of his own crew for trying to escape. Yet by April of 1724, Fillmore and several other captives aboard Phillips’ ship were desperate enough to fight back.

Fillmore quickly learned that the pirate captain John Phllips was not to be challenged. One of the vessels Phillips’ crew captured in early 1724 had some geese and hogs aboard, which presented the tasty prospect of fresh meat to men who spent virtually all of their time at sea eating dried and salted food. Phillips demanded the live animals, but the ship’s captain refused and struck Phillips with a handspike. Phillips quickly drew his sword and plunged it into the captain, killing him. This was only months after Phillips killed one of the initial members of his own crew for trying to escape. Yet by April of 1724, Fillmore and several other captives aboard Phillips’ ship were desperate enough to fight back.

The break they were looking for came on April 14, off the coast of Nova Scotia. The pirates captured a sloop, the Squirrel, and took the new vessel as their own, moving their equipment, supplies, and weapons over the next day. The pirates allowed most of the captured sloop’s crew to go free, but kept its young captain, Andrew Harradine, from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Within a day of Harradine’s capture, Fillmore quietly approached him with the idea of planning an attack on the pirate crew. There were seven captives in on the plot, including Fillmore and Harradine, and it seemed possible that they might be able to overpower the eight pirates if circumstances were right.

Three days later, they were. The pirates were in an especially raucous mood and had spent most of April 17 celebrating their recent successes, eating and drinking late into the night. Sometime that evening, Captain Phillips gave two orders: for a captive named Edward Cheesman, the carpenter, to bring his tools up onto the deck so he could make some repairs early the next morning, and for the crew to make sure they took an observation of the sun at noon the next day to determine their position at sea. This gave the captives the opportunity they needed. Late that night, the pirates finally passed out. Some went to sleep in Phillips’ cabin near the back of the ship and two others — the quartermaster John Rose Archer and a pirate named William White — lay down in the cook’s area near the fireplace on deck. The two of them must have been drunk beyond comprehension because after they’d been asleep for a while, Fillmore was able to sneak up to Archer and White with a hot stick from the fire and burn the soles of their bare feet so badly that they would not be able to walk on the deck the next day. But the captives apparently decided not to try and overpower the pirates in their drunken state that night, perhaps wanting to wait until daylight.

When morning broke, the captives began their work, but there was no sign of the pirates, who remained fast asleep. Finally, close to noon, Phillips and several other men stumbled out of the cabin. One of the pirates got ready to measure the angle of the sun with a wooden quadrant, its arm-length slats connected in the shape of a long and narrow triangle. Cheesman was standing with him. The sails were full and the ship was moving through the water at a good rate, with one of the captives at the helm. Fillmore and Harradine were standing on the deck with several of the other pirates. Cheesman had intentionally left a broad axe resting on the deck after finishing his work that morning, and Fillmore stood casually spinning the broad axe with his foot.

In an instant the men attacked. First Cheesman grabbed the pirate standing next to him and threw him overboard. Fillmore bent over and picked up the broad axe at his feet and bore down on another of the pirates who was busy cleaning his gun, striking him over the head and killing him. Alarmed by the shouts and commotion on deck, Phillips came out of his cabin to see what was going on. The captive who was manning the tiller, a Native American named Isaac Lassen, jumped at Phillips and grabbed his arm while Harradine struck him over the head with an adze. Finally, two French captives jumped a fourth pirate, killed him, and threw him overboard.

In less than two minutes’ time, four of the most active pirates on the crew, including Phillips, had been killed. The remaining pirates were now far outnumbered and immediately surrendered. The captives took control of the ship and headed home, arriving in Boston on Sunday, May 3. The captives’ stunning overthrow of the pirate crew fascinated the town. The Boston News-Letter, the Boston Gazette, and the New England Courant each published accounts of how Fillmore, Cheesman, and Harradine brought down Phillips and his men. One report even suggested that the captives brought Phillips’ head back to Boston with them. The pirates were put on trial nine days later, on May 12. Two members of Phillips’ crew, William White and the quartermaster John Rose Archer, were convicted and hanged. After the execution, the bodies of White and Archer were hauled back out to Bird Island in Boston Harbor. White was buried on the island, while Archer’s body was hung there in a gibbet “to be a spectacle, and so a warning to others.”

In less than two minutes’ time, four of the most active pirates on the crew, including Phillips, had been killed. The remaining pirates were now far outnumbered and immediately surrendered. The captives took control of the ship and headed home, arriving in Boston on Sunday, May 3. The captives’ stunning overthrow of the pirate crew fascinated the town. The Boston News-Letter, the Boston Gazette, and the New England Courant each published accounts of how Fillmore, Cheesman, and Harradine brought down Phillips and his men. One report even suggested that the captives brought Phillips’ head back to Boston with them. The pirates were put on trial nine days later, on May 12. Two members of Phillips’ crew, William White and the quartermaster John Rose Archer, were convicted and hanged. After the execution, the bodies of White and Archer were hauled back out to Bird Island in Boston Harbor. White was buried on the island, while Archer’s body was hung there in a gibbet “to be a spectacle, and so a warning to others.”

After the trial, Fillmore was reportedly given Captain Phillips’s sword, which in time would become a possession of his great grandson, Millard Fillmore, who became the thirteenth president of the United States in 1850 following the death of Zachary Taylor. For his part, after surviving the brief voyage with Phillips’ pirate crew, John Fillmore returned briefly to Ipswich and then moved to Franklin, Connecticut, where he spent most of the remainder of his life. His headstone remains today at the Plains Cemetery in Franklin.

At the Point of a Cutlass was released in June 2014 and is on sale now.